Call it the Laundromat. It’s a complex system for laundering more than $20 billion in Russian money stolen from the government by corrupt politicians or earned through organized crime activity. It was designed to not only move money from Russian shell companies into EU banks through Latvia, it had the added feature of getting corrupt or uncaring judges in Moldova to legitimize the funds. The state-of-the-art system provided exceptionally clean money backed by a court ruling at a fraction of the cost of regular laundering schemes. It made up for the low costs by laundering huge volumes. The system used just one bank in Latvia and one bank in Moldova but 19 banks in Russia, some of them controlled by rich and powerful figures including the cousin of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

It may be the biggest money-laundering operation in Eastern Europe – a virtual laundromat operating through banks and companies connected to powerful people in the region.

It may be the biggest money-laundering operation in Eastern Europe – a virtual laundromat operating through banks and companies connected to powerful people in the region.

Between 2010 and early 2014, organized criminals and corrupt politicians in Russia moved US$ 20 billion in dirty funds through this laundromat’s complex cleanse-and-spin cycle made up of dozens of offshore companies, banks, fake loans, and proxy agents. The process was then certified as clean by judges in the tiny Republic of Moldova. The newly cleaned funds were then spread across Europe.

Now law enforcement and prosecutors in Moldova are investigating the system.

„Many judges and executors may go to prison” said Vasile Șarco, the head of the Money Laundering Prevention Unit in Moldova, which has been looking into the case since December.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) has worked through the system’s intricacies to uncover the methods and the partners who ran The Laundromat. The banks and companies involved are run by managers and board members that include well known businessmen, a cousin of Russian President Vladimir Putin, and persons said to be close to the KGB.

The key to the system was the involvement of Moldova, a country caught between its aspirations to join the European Union and its history of close ties to Russia. The scheme used Moldova to both provide legal protection against regulators through the country’s judicial system and a means to inject the illegal money into the European Union’s financial systems.

The Cleaning Cycle

The eternal problem with dirty money is explaining where it comes from. Crime is mostly a cash economy, and mobsters or dirty government officials can end up with massive piles of cash they don’t want to explain to anybody—especially tax officials.

The Laundromat was designed to create the illusion of business activity to explain the source of the money, backed by a court which signed off on the transactions to make them legitimate. The businesses, however, were phantom companies shielding the real owners.

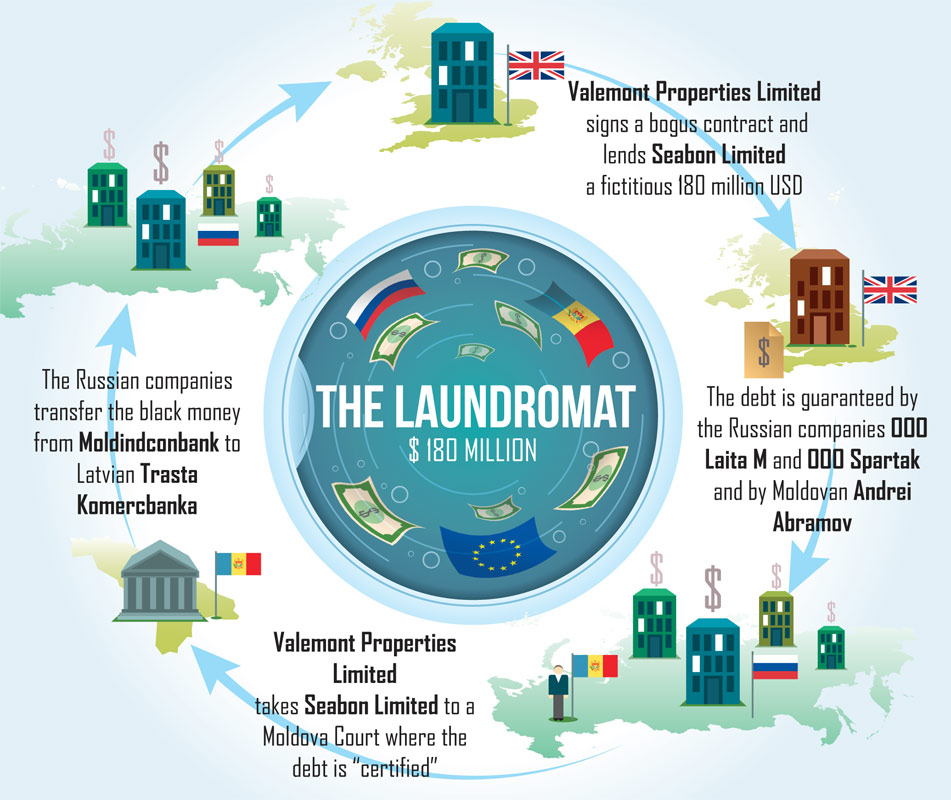

A typical transaction began with two companies, often based in the United Kingdom and with their true ownership obscured in the offshore mists of a tax haven. The companies sign a bogus contract in which one agrees to lend the other large sums, although no money ever actually changes hands. It is likely that both companies are owned by the same owner but that ownership is hidden behind “proxy” figures.

The tax haven of choice in this operation was Belize, and the sums involved in each transaction were huge, ranging from US$ 100-800 million. The contracts in each case stipulated that the debt was guaranteed by companies in the Russian Federation, almost always run by a Moldovan citizen. This Moldovan gave the operation access to the courts in Moldova, which would ultimately permit the movement of the dirty money into the legitimate banking system.

The next step was for the “borrowing” company to refuse to repay the debt to the “loaning” company, thereby shifting the debt to the Russian companies who had guaranteed the loan. The “loaning” company then would take the matter to court in Moldova where a judge would issue an order “certifying” the debt as real and ordering the Russian company to pay.

Then the Russian company would transfer dirty money into an account set up by the “loaning” company. For every case, the money was sent to an intermediary bank called Moldindconbank—an institution connected to one of the country’s most powerful businessmen.

Finally the money was wired to the “loaning” company’s account, which was always at the Latvian-based Trasta Komercbanka.

And once it is in Latvia, voila! It is in the European Union, backed by a court order and clean and ready to use.

The OCCRP investigation found that 19 Russian banks, some already being investigated for money laundering, used The Laundromat.

Judging the Judges

More than 20 judges in 15 Moldovan courts helped launder the money. Over three years, they issued more than 50 court orders certifying about US$ 20 billion in debt. This is a staggering amount for a country such as Moldova that had a GDP of just under US$ 8.5 billion in 2013. Some of these judges are now under investigation while others have resigned.

The Laundromat opened for business on Oct. 22, 2010, when a British company called Valemont Properties Limited filed suit in a court in the Moldovan capital of Chișinău against the guarantors of a loan it had made to another UK company. The holders of that guarantee were a Moldovan man, Andrei Abramov, and two Russian companies: OOO LaitaM and OOO Spartak.

OCCRP found Abramov at his workplace, the Chișinău Airport. He said that he got involved with the Russian companies in 2010, right after he completed his civil aviation studies and was looking for a job.

OCCRP found Abramov at his workplace, the Chișinău Airport. He said that he got involved with the Russian companies in 2010, right after he completed his civil aviation studies and was looking for a job.

„A friend from Canada put me in touch with a Ukrainian citizen whose surname I don’t recollect. We met in a Chișinău restaurant and he told me he has companies in Russia, Ukraine and the United Kingdom.” – Andrei Abramov.

Abramov said the man told him he had a consultancy firm and wanted to open a branch in Moldova with Abramov as the manager.

„It never happened though. I worked for them for four months and all I got was $100.”

Abramov said he was directed to go to Chișinău’s main bus station, where he received packages of documents from Ukraine. Then he would send them onward to Russia.

He said he was disappointed that the promises made about his new job were not kept. “I signed a document once for a court in Rîșcani where I said that I don’t have any objection regarding an ongoing trial,” he said.

OCCRP found out from border police documents that Abramov visited Ukraine four months before the Valemont Properties court case. Other Moldovan citizens used in Laundromat operations frequently travelled on the Chișinău-Moscow route.

The court case involving Abramov was tried by a Moldovan judge, Gheorghe Gorun, who certified the debt and ordered the Russian companies and Abramov to pay up. Gorun’s decision was enforced by a Moldovan judicial executor, Anatolie Chihai, who acted as a go-between.

Chihai opened an account with Moldindconbank to receive money transferred from Abramov’s Russian company, which was then transferred again into the Trasta Komercbanka account of Valemont Properties in Latvia. This money route–Russian banks to Moldinconbank to Latvian Trasta Komercbanka–was to be used in all of The Laundromat’s money transfers.

Trasta officials refused to comment on the cases.

OCCRP obtained banking statements that show multiple money transfers into Chihai’s bank account. Both Russian companies, OOO LaitaM and OOO Spartak, transferred billions of rubles that were exchanged for British pounds and sent onwards to Valemont. The money came to Moldova from accounts in two Russian banks, EB Transinvestbank OOO and KB Inkredbank.

Valemont Properties is involved in other Moldovan court cases aimed at recovering debts. In each case, the British company was represented by Ukrainian Bogdan Kuchay, 32. He is a director of OOO Prime, a Russian company founded in 2012, which lists as sole shareholder a Belize offshore company called Denison Limited. Denison has sued debtors in the same manner as Valemont.

Kuchay is involved in other controversial court cases as well.

Bad Loans

Ukrainian Bogdan Kuchay became a main actor in another judicial case in Moldova in 2013 after he and fellow Ukrainian Roman Rybchenko, 22, acquired seven shares or 0.00014 percent of the share capital of the Moldovan insurance company, Compania Internațională de Asigurări S.A “ASITO”.

Investigators say they acquired these shares for the sole purpose of suing the company and blocking its bank accounts so that ASITO could not pay pensions to more than 8,000 Moldovan retirees.

A Chișinău judge, Svetlana Garstea-Bria, accepted Kuchay’s suit as valid and pensioners stopped getting money. The case is still on trial while the Moldovan National Commission for Financial Oversight asked the Superior Council of Magistrates, the governing body over Moldovan courts, to sanction the judge who accepted the case.

The Superior Council of Magistrates (SCM) concluded in a May 27 statement that many rulings in debt recovery cases were issued illegally. The SCM says that the judges based their judgments solely on documents that had not been properly authenticated or notarized, a practice contrary to normal court procedures.

OCCRP reporters met with Valeriu Gîscă, one of the judges who issued five judgments for The Laundromat, in a parking lot next to the Moldovan Government building. He came to the meeting in a black SUV, wearing casual clothes. His rulings certified no less than US$ 2.1 billion that left Russia for offshore company accounts before he resigned in 2012.

OCCRP reporters met with Valeriu Gîscă, one of the judges who issued five judgments for The Laundromat, in a parking lot next to the Moldovan Government building. He came to the meeting in a black SUV, wearing casual clothes. His rulings certified no less than US$ 2.1 billion that left Russia for offshore company accounts before he resigned in 2012.

According to SCM, Gîscă put in his resignation request on grounds of ill health on Nov. 22, 2012. On Dec. 18, Gîscă issued one final Laundromat judgment for half a billion US dollars, and three days later he was relieved of his duties. Now a lawyer, Gîscă says his rulings followed the law and did not hurt the Moldovan financial system or any bank and just affected one citizen.

“Each time, a guy from Chișinău presented me with paperwork showing that the parties involved had no objections in the court case. These documents were authenticated at the highest possible levels,” he said adding none of his rulings have been overturned.

“If someone laundered money and used us, it is up to the Moldovan law enforcement to prove it. I don’t know who could possibly be behind it and I had no idea that other judges issued the same kind of rulings in Moldova,” Gîscă said.

OCCRP tried to talk with Svetlana Mocan, a judicial executor who enforced many of The Laundromat rulings. Nearly US$ 17 billion in transfers went through her bank account. Mocan would not meet with reporters or answer questions. She said only in a phone conversation: „I don’t have the right to give you information. I won’t give you any.”

Șarco, who leads the Money Laundering Prevention Unit, said the rulings did not follow the law and were not based on proper documents. “We are also going after persons in the banking system. We have three ongoing penal cases and another two are about to be initiated. There are two penal cases opened in Latvia and Estonia, too.”

Șarco said his office started a case against an executor in February of this year and in March arrested another executor.

On July 22, Moldovan Prime Minister Iurie Leancă proposed a set of laws that, if Parliament passes them, would end impunity for judges implicated in money laundering.

Russian Companies, Moldovan and Ukrainian Proxies

Moldovan law enforcement believes that more than 90 companies registered in the Russian Federation were involved in The Laundromat system, making thousands of transfers into bank accounts in Moldova and, from there, onward to offshore companies’ bank accounts.

OCCRP investigated the ownership of some of these companies. It found a number of cases in which directors and shareholders were citizens of Moldova and Ukraine. They appear to be proxies, fronting for the real people behind the money schemes. One example was OOO Proffstandart, a Russian company, listed with four other commercial entities in Moldovan courts with a debt of half a billion US dollars to the Scottish company, Westburn Enterprises Limited.

The majority shareholder of OOO Proffstandart is Ruslan Siloci, 31, from Căușeni, a small town 70 kilometers from the Moldovan capital and 40 kilometers from Tiraspol, the main city in the separatist region of Transdniestr. Căușeni is the hometown of a powerful businessman, Veaceslav Platon, whose father, Nicolae, is head of the local Moldindconbank, the main Moldovan bank engaged in The Laundromat’s money transfers.

Siloci lives in the outskirts of the city in his grandparents’ home. When OCCRP reporters visited on June 19, the door was locked.

„He comes and goes,” said a saleswoman in a nearby shop. “He is a good boy. Are you here to take some money from him? I owe him US$ 100.”

Just then the women pointed out Siloci in a blue Mercedes.

Siloci lit up a cigarette and asked if we’d tried to get in touch with him day before. „My wife told me someone was looking for me,” he said. “I just got back from Ukraine. I went to Odessa to pick up some goods. I’ll make US$ 300-400 for this.”

Siloci said Proffstandart has been closed.

“I have different businesses now. I’m dealing with construction materials. It’s hard, not easy to start over.”

“I have different businesses now. I’m dealing with construction materials. It’s hard, not easy to start over.”

OCCRP asked Siloci why his company got entangled in debt. He said he was approached by “clients” who offered him a money making deal.

„I’ll clarify one thing for you. This is how business is done in Moscow. There’s nothing new about it. They looked me up, they found me for the transfers. It wasn’t just me, there were many others.” – Ruslan Siloci.

Siloci would not talk about how much money he earned as a proxy. “It’s confidential, a trade secret. Nobody will tell you how it worked. I know there is an investigation on this in Moldova but nobody called me up from the prosecution.”

OCCRP found that Siloci is also sole shareholder of a Moldovan company, Prodpozitiv SRL, against which authorities lodged a criminal case in 2009. He and his firm were suspected of smuggling meat. „This case is in court now. It will take forever to judge,” he said. “I just brought pork instead of chicken from Russia. That was all. I’m reorganizing the company right now. I have a few shops right now here in Causeni.”

If I Had Half a Billion…

Evgheni Vîborov is another Moldovan citizen involved in the Westburn scheme. The 33-year-old driver for an express delivery service in Chișinău is listed as a shareholder and director of the Russian firm OOO Komtehkomplekt. He denied doing anything wrong and was worried to hear about his involvement in a suit over The Laundromat.

Evgheni Vîborov is another Moldovan citizen involved in the Westburn scheme. The 33-year-old driver for an express delivery service in Chișinău is listed as a shareholder and director of the Russian firm OOO Komtehkomplekt. He denied doing anything wrong and was worried to hear about his involvement in a suit over The Laundromat.

„I was in Moscow in 2009 when someone I knew there advised me to buy a company,” Vîborov said. “I was taking care of computers and other technical equipment. In about 2012 I shut down the company and came back to Chișinău. I believe I have given power of attorney to someone but it was long ago and I don’t remember.

“Nobody gave me money and nobody looked for me,” Vîborov said. “I wouldn’t have had to mortgage my house, I’d have my own car and I wouldn’t be working as a driver if I had received money. It never crossed my mind that my company is involved in such a court case,” said Vîborov.

“If I’d had half a billion I’d have donated it to an orphanage.”

Moldovan Parliament member, Nae-Simion Teodor Pleșca, bought Vîborov’s neighboring apartment for US$ 53,500 to expand his own apartment. Vîborov still uses it as his official address.

“Evgheni is a troubled boy. I believe he was used in money laundering. I think someone tricked him,” Plesca said.”

The $20 Billion Bank in the Country of the Poor

Law enforcement reports obtained by OCCRP indicate that one of the oldest and biggest banks in the Republic of Moldova, Moldindconbank, has been used in the biggest money laundering operation in Eastern Europe in recent years.

The operation, dubbed the Laundromat, involved about US$ 20 billion moving from Russia through the bank’s accounts over the past three years.

The staggering amounts of money pouring through Moldindconbank and other Moldovan banks seem to contradict the United Nation’s characterization of Moldova as the poorest country in Europe.

It is not the first time that Moldovan banks have been used in large-scale money laundering originating in Russia.

Riddled with corruption and situated at the eastern border of the European Union, the former Soviet country is the ideal stopover for dirty Russian money on its way to the European Union or Switzerland. Another Moldovan bank, Banca de Economii a Moldovei (BEM), was involved in another prominent money-laundering case investigated by OCCRP, the Sergey Magnitsky case.

Moldindconbank’s origins go back to Stroibank, a bank established in 1959 in what was then the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The Moldovan subsidiary of Stroibank became Moldindconbank in October 1991. It was meant to primarily finance the country’s industries and construction businesses.

Under Communism, all banks in Eastern Europe were state-owned. After the fall of the USSR, things got a lot murkier. Moldinconbank’s current ownership is difficult to discern, with offshore companies owning a good chunk of the bank.

Moldindconbank was also named in a previous money laundering case. In December 2008, the bank received a US$ 180,000 fine for non-compliance with the anti-money laundering regulations.

The bank denies any involvement in money laundering operations.

The Laundry Cycle, From Start To Finish

Ruslan Milchenko, formerly with the Russian police, today heads the anti-corruption agency Analitika and Bezopasnost (Analyses and Security) and knows all about Moscow-style money laundering.

In an interview with reporters for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), Milchenko explains how the system works:

OCCRP: Could you please explain to us how money launderers work, step by step?

Milchenko: Money-laundering schemes have a number of layers. I know some bankers who work, let’s say, in the middle of this pyramid. They have relationships with about 10 banks.

So imagine that you have US$ 100 and its origin is doubtful. You just go to such a banker and tell him that you need this money somewhere in Hong Kong. If you don’t have a company or a bank account there, the banker will sell you one – they have plenty of companies all over the world.

They buy such entities from law firms, which register shell companies.

So you give 100 dollars to the banker and in a couple of days you receive 96 or 97 dollars, depending on the commission (charged) in Hong Kong, or any other place in the world. And you as client will not know the route of your money – that is the money launderer’s job.

They have dozens of companies in Russian banks. So using just one laptop with a bank-client program, they move your money from one bank to another, from one company to the next one.

OCCRP: Do the banks engaged in the money transfers know what is going on?

Milchenko: Of course. Money launderers need to pay commissions to each bank where they are allowed to work. And your four dollars commission is split between different banks. The banker you worked with will earn, in the end, 1.5-2 percent from your 100 dollars. Yes, it’s a difficult business, which is profitable only if you have many clients and good volumes.

OCCRP: How profitable?

Milchenko: People like my acquaintances are not millionaires. But those who are on the top of the pyramid are billionaires. These people can afford to buy banks after banks that then become platforms for huge money withdrawals abroad.

It’s like with waterfalls – many, many small rivulets form, in the end, a huge flow. So my mates who work with these rivulets have a turnover of hundreds of millions, those who control the flow deal with hundreds of billions.

There are not more than five to seven people in Russia who work with such volumes of money. Such bankers are very well politically connected and protected by special services.

Iurie Sanduta, Ion Preasca (RISE Moldova), Roman Anin, (Novaya Gazeta), Mihai Munteanu, Paul Radu, Miranda Patrucic (OCCRP), Victor Ilie (RISE România), Arta Giga (Letonia), Vladimir Kostic (CINS Serbia)